However, I think it will work here: and feel it needs to be said: so I'm publishing it myself. Comments appreciated.

IN

PRAISE OF FIDDLING

"Don't

fiddle", they say; "less is more". And I suspect this

is why I'm seeing more and more paintings in exhibitions which just

aren't finished at all. The advice has been taken so literally that

oil and acrylic paintings are left thin and scratchy, looking like

nothing so much as a paint-by-numbers effort (where the paint is thin

because they give you too little of it, and most p-b-n'ers stick

rigidly to the lines).

Thing

is, this is good advice for watercolourists, on the whole. Once

you've applied a wash, the best thing to do with it is often to leave

it alone - fiddle with it and you get back-runs and mud.

But

there are reasons for this. Watercolour is a medium which relies on

its transparency and purity of colour. There are opaque colours in

watercolour, but many of us avoid them because they can quickly ruin

the light, evanescent appeal of a watercolour painting.

Oil

and acrylic, save in special circumstances (glazing, particularly)

are not primarily employed for their translucent qualities. They can

certainly be used as such, but the usual approach with both is

layering of one colour over another, or one tone over another to

achieve depth and form.

So

it should go without saying - but it doesn't - that you aren't going

to get the best out of these opaque, layering pigments if you don't

actually layer them: this doesn't mean you have to add finicky,

nit-picking detail - that is true "fiddling"; but it does

mean that the subtlety of oil and acrylic is best exploited by a

process of addition; a painting may actually accrete layers - we can

work them up in stage after stage, each one strengthening the image,

establishing form, shape, tone, shadow, light.

Oils

and acrylics are, in short, USUALLY additive rather than subtractive

media - whereas in watercolour you might, as a matter of your usual

technique, take something out, in oil and acrylic you're generally

going to be doing the reverse. Yes, you'll sometimes find you have

to take the sponge, cloth or knife to the paint, to remove a claggy

mess of mud: but this isn't something you'll actually be planning or

hoping to do. It may form part of your technique, but only because

you haven't yet mastered it.

There

are of course those of the plein-air

persuasion, who very reasonably point out that there's no way they

can apply careful layering in oil, because it just doesn't dry fast

enough out there in the field - in fact, it IS possible, but only

with a delicate and at the same time sure touch. Even so, one takes

the point - yes you can work over several days; or finish off your

plein-air study in the studio; or of course use the plein-air sketch

as the basis for a larger painting to be tackled indoors. But the

typical plein-air work requires mixing the right colours to start

with, and getting them down in relatively quick, unrehearsed, and

unfussed strokes of paint. Such paintings have great immediacy -

they might

however sacrifice subtlety. Many of us, perhaps most of us, sketch

en plein air, and either finish the painting in the studio, or start

a new, larger one, using the sketch as our guide.

One

of my recurring nightmares is that I drop dead in the middle of a

painting - because most of my opaque work reaches a stage that might

generously be described as god-awful: a stage at which you could only

think the poor old chap's lost his touch; to think it should have

come to this, etc.... But then, it's a work in progress - true, if a

watercolour starts to look as though something horrible has happened,

it probably has. But oils and acrylics - mine, anyway - nearly

always go through the "oh dear, surely he can't have meant to do

that?" stage, and by way of illustration I offer an acrylic

painting of mine that did, in the end, represent what I had in mind,

but had rather painful birth pangs before it got there.

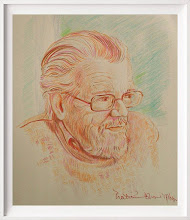

Here's

the sketch – the tones are broadly indicated, plus as much of the

detail as I felt necessary:

Figure

1

I

toned my board with a mixture of Burnt Sienna and a touch of red, to

produce a map of the tones; no detail – just putting the big shapes

in. And I roughed in the sky with ultramarine and white. I decided

at this point that I didn't want a complicated land-mass and a busy

sky – if I do this again, I think I might make the sky more

interesting, since it occupies quite a large area of the painting.

Figure

2

At

this stage, it doesn't look too bad at all: the profiles of the cliff

are about right; I've mixed ultramarine and burnt sienna for my

darks, just placing the foliage areas. In fact, if I'd been a bit

more careful with these shapes and darks, I could even have glazed

over the top to finish the painting in half the time (in theory at

least).

Fig

3

Had

I been going to pursue that route, this is the stage on which I'd

have based it: just firming up the darks, lightening the lights, and

refining the drawing, then adding transparent glazes. However,

that wasn't what I was after: I wanted a rather more rugged look than

that approach would have given. So rather than refine shapes, I

built the painting up from the broad shapes I'd already established –

remember, I had my sketch to show me those details I was about to

cover with opaque white, mixed at this stage with varying amounts of

ultramarine, burnt sienna, and yellow ochre.

This

is the stage at which I would not have wanted to drop dead (any other

time, fine: but not just now). Because it looks … well, vile,

don't you think? But – I've got the big shapes; I've got the

build-up of opaque paint which will give me my textures, especially

in the near cliff. What have I got to do now? Well – this was

perhaps the most important stage of the painting. It doesn't look

it, maybe. But all I've really got to do now is – fiddle. Take a

good, chisel-edged flat, and a fairly large rigger, and turn these

blocky shapes into convincing rocks and trees.

And

this, completed in one stage, is it. I've removed the fence from the

bottom left (without which I would never have stood on that bit of

cliff, but it wasn't needed in the picture). I've added a little

chunk of cliff beyond the first promontory, which isn't there in

reality, but the composition needed it. And using no more extra

colours than viridian, a little Naples yellow, and a touch of prism

violet, I've just built up detail by, well, fiddling. The hard work

was done at Stage 4 – you've GOT to get those basics down, however

awful they look, before you can put clothes on them.

There

are things I would do differently if – when – I tackle this

again: a bigger canvas (this one is 30 by 40cm); a livelier sky; and

next time I might actually try getting to Figure 3, establishing

some lighter lights, and apply transparent glazes. And I might do a

version in oil, which lends itself better to the textured approach

(especially if you're using only paint, and not any kind of texture

paste). But without a bit of fiddling with detail, I'd have had a

different picture. So long as you remember that the time comes when

the fiddling has to stop.